An old African proverb says, “In the jungle, there are many ways to die, the most dangerous being the monkey’s dance and the peacock’s strut.”

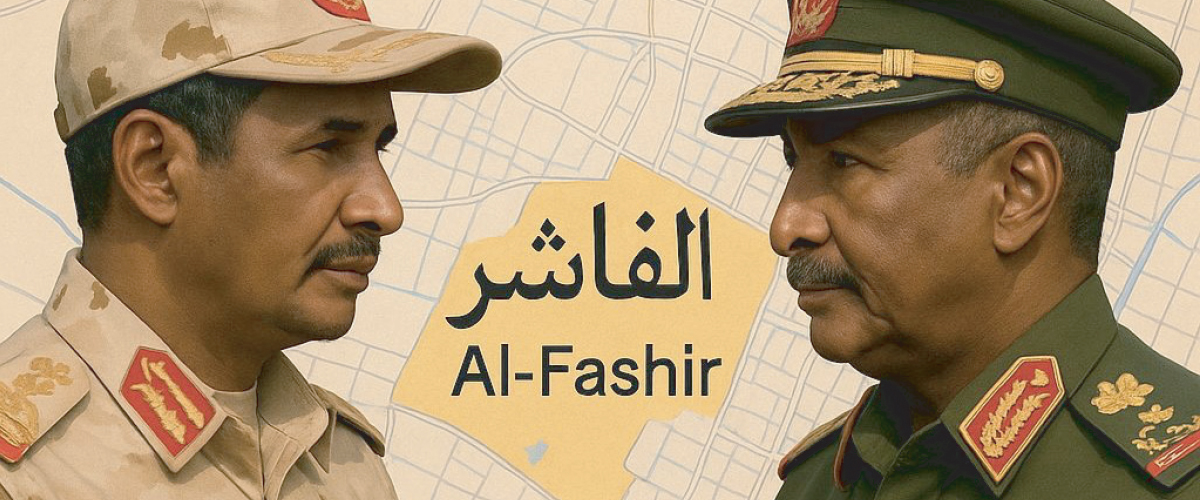

The leadership of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) understands that the Battle of El Fasher is the final chapter in their bloody performance—one that history will record as part of Sudan’s national narrative. And even if this battle does not serve as the final nail in their coffin, it is certainly the moment of reckoning long awaited by souls who once chose to confront a brutality Sudan has never witnessed in its modern history.

Since the events of April 15, 2023, all regional and international actors have bet on the fall of El Fasher, the capital of North Darfur State, to the RSF—especially after the militia took control of most of the other states in the region. However, El Fasher’s resilience has proven to be the path to the battle for Khartoum. The remapping of Sudan’s post-Bashir future was not determined solely by the battle for Khartoum, but rather enforced by the battle for El Fasher. The rapid developments in El Fasher shed light on a complex political-security-intelligence struggle facing Sudan’s military institution, and recent events indicate it is navigating it with steadfastness.

After the liberation of the capital, Khartoum, and the Sudanese leadership’s shift westward to cleanse the Darfur region, three perspectives emerged regarding the Battle of El Fasher:

🔆 The Vision of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF):

The RSF believes that its continued existence in post-Bashir Sudan hinges on maintaining control of El Fasher. Anything less may lead to a state of internal erosion, which the militia already senses spreading through its deteriorating structure. They fear this could evolve into what is known in security and intelligence studies as “structural predation.” From the RSF’s security and intelligence perspective, El Fasher represents their last hope to restore the confidence of the ideological base they claim to represent. It is the only gateway that might convince regional and international actors to eventually recognize their so-called government. Moreover, it serves as a true lifeline for reorganizing the militia’s internal structure and recalibrating its strategy to play a new political role in Sudan and its regional neighborhood.

The RSF leadership is well aware that its presence in the minds of most of its cadres and grassroots supporters is on the brink of turning into a disguised rejection marked by disillusionment. This is evidenced by the public statement of “Nazir Madoubi,” directed at the militia’s leadership, in which he stated verbatim: “If the Sayyad convoy enters East Darfur State, I will surrender to the army, and I will not allow a war inside Ed Daein.” This clearly indicates a growing lack of confidence in the militia’s ability to win the battle of El Fasher, let alone maintain the loyalty of its social base to the end. This, in turn, opens the door wide for questioning the true nature of the ideological foundation upon which the RSF’s social and operational base was built—one which the battle of El Fasher seems determined to expose, along with its flawed leadership.

🔆 The Vision of the Sudanese State:

The leadership of the Sudanese national state believes that the rapid developments on the Sudanese scene will go beyond the city of El Fasher. The deep divisions imposed by this war on the very essence of the Sudanese state have, in fact, created a historic opportunity in an exceptional moment for a leadership fortunate enough to rise as the driving force for fully reclaiming and rebuilding the state from within. From now on, there will be no Sudan without a fully liberated Darfur—free from outlawed, multinational, and multi-loyalist militias.

Thus, the Sudanese leadership has crystallized its vision that the Battle of El Fasher is the only path to uproot the project of national fragmentation at its core. The Sudanese Armed Forces’ success in tightening their grip on El Fasher, thwarting all RSF operations aimed at breaching the city’s perimeter, and their recent control over the towns of Al-Hammadi, Al-Dibibat, and Taybah has significantly weakened the RSF’s military-security apparatus, which was intended to form the nucleus of the so-called “Peace Government Army.”

This success has also deepened the internal morale fracture within RSF ranks and convinced many political, partisan, military, security, and intelligence figures to defect from the militia. These individuals declared their split or their intention to return to the national fold, motivated by their vision for a post-war Sudan. They believe that the Sudanese crisis and its pivotal developments have given birth to a new Sudan with a new people—one that carries only the memory of the old “Ingaz” (Salvation) era. While some may nostalgically yearn for that period, they are not seeking its revival. This shift is largely due to the evolved concept of the homeland among Sudanese citizens, which has led to the formation of forward-looking visions that could not have emerged without the painful labor Sudan has endured.

🔆 The International Perspective:

The international community now recognizes several emerging truths about the Sudanese situation:

First: The Sudanese military institution after the liberation of Khartoum is not what it was before. All regional and international stakeholders now understand that the military doctrine adopted by the Sudanese Armed Forces is no longer the traditional one that most armies are built upon. What Sudan has endured over the past three years has been sufficient to reshape the national outlook of all sovereign institutions for the Sudan of the future.

Second: The Sudanese military establishment and all its security branches are preparing for challenges far greater than merely defeating multinational militias with diverse supplies and agendas. This is a unique calculus understood only by truly sovereign national security institutions—those that operate independently of foreign oversight and management.

The global view toward the RSF’s entity and leadership has now largely converged—even if some actors remain silent or tacit in their stance. Still, that doesn’t negate their underlying conviction, which has coalesced around one central truth:

The RSF no longer draws its strength or legitimacy from within Sudan, whose people are now formulating their own vision based on the lived experience of the recent war and its outcomes. While this truth may have been obscured during the “Ingaz” era, the battle for dignity, which began in April 2023, has come to reveal and clarify it for all.

Possible Scenarios for the Battle of El Fasher:

♦ Scenario One: “Sudanese Army Gains Full Control of the Darfur Region”

This scenario is contingent on three key factors:

- Acquisition of advanced military equipment by the Sudanese Armed Forces

- The fall of Ed Daein

- Continued defections and desertions from the RSF’s ranks.

The fall of Ed Daein to the Sudanese Armed Forces would destabilize the RSF’s political and security balance—especially given that Nazir Madoubi explicitly stated: “If the Sayyad convoy enters East Darfur State, I will surrender to the army.” Should this happen, it would immediately shift the social dynamics across all towns and states in Darfur, removing obstacles for the Sudanese Army to continue its military operations across the region. In this case, the army would have solid control over two state capitals: El Fasher (North Darfur) and Ed Daein (East Darfur)—the latter serving as a strategic link between western and central Sudan and a stronghold of the Rizeigat tribe.

(The main challenge to this scenario lies in the complex tribal interconnections between Darfur’s population and neighboring Chad, which would require a specialized strategic approach to effectively reshape realities on the ground.)

♦ Scenario Two: “El Fasher Falls to the RSF”

This scenario depends on several key elements, the most critical being:

- The fall of El Fasher from within via sleeper cells cooperating with the RSF. (This is a strategy the RSF is actively pursuing, especially after the death of Major General Ali Yaqub, which significantly altered their perspective on the city.)

- Draining the Sudanese Army through attritional warfare in unpredictable battlefields. (The RSF command is making, and will continue to make, great efforts to achieve this.)

What hinders this scenario is the Sudanese leadership’s firm belief that failure to secure El Fasher would mean advancing the agenda of national division, reviving hopes for a parallel government, and eroding public confidence in the military establishment. (This is a scenario that Khartoum fears deeply and will do everything to prevent.)

♦ Scenario Three: “El Fasher Remains Under Sudanese Army Control”

In this case, skirmishes between the army and the RSF would continue, exposing all cities and areas in Darfur to alternating waves of attacks and retreats. This would have a negative impact on the stability of areas under the control of both parties, turning even the safest zones into legitimate targets and worsening the humanitarian crisis.

This prolonged conflict would likely trigger international intervention, opening the door to further scenarios—including the potential secession of Darfur and the beginning of its implementation.

♦ Scenario Four: “Partition of the Region”

This scenario envisions a division of Darfur between the Sudanese Army and the RSF. In light of the ongoing arms race between both sides, one may gain the upper hand on the battlefield. To avoid internationalization of the conflict—which could lead to undesirable outcomes—both sides might reach an agreement to divide the region, with the more dominant party receiving control over three out of the five Darfur states.

(Although this scenario remains unlikely due to the Sudanese Army’s commitment to fully eliminate the rebels and its refusal to negotiate with them, and the RSF’s insistence on retaining all its grassroots support areas, the evolving situation in Darfur leaves all possibilities open.)

Supporting Practical Efforts to Strengthen the Role of the Nation-State in Post-Bashir Sudan:

♦ Influencing the Popular Base of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF):

Most of the RSF’s social base now lives in a state of suspicion and uncertainty, especially as reports surface about defections among the Misseriya tribes due to the Sudanese Army’s progress in Kordofan and the escalating clashes with the RSF.

To capitalize on this, figures like Mohamed Saleh Al-Amin Barka—a key early ideologue of the Atawwa movement who was initially instrumental in Hemedti’s tribal recruitment strategy but later sidelined and exiled after the 2019 fall of the Bashir regime—could be mobilized. Barka is known for his moderate national stance.

Communities within RSF strongholds have started to realize that Hemedti’s recruitment of specific tribes was not for building a national project but rather to serve personal ambitions. As Sudanese writer Youssef Abdel Manaan once said:

“Hemedti’s project in Sudan has nothing to do with national interests or internal affairs. It is a result of overlapping agendas of various actors who share Hemedti’s personal ambition to rule Sudan and turn it into a kingdom. His motivations are personal—not national.”

This realization explains the growing number of defections and desertions from RSF forces to unknown destinations.

♦ Politically:

Support Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s initiative on the Sudanese file. Khartoum should leverage Ankara’s influence, particularly with the anticipated visit of U.S. President Donald Trump to the Gulf states. Ankara possesses a unique ability to differentiate between long-term strategic alliances and what the French call “Diplomatie transactionnelle”—or “transactional diplomacy”—a label frequently associated with Trump’s administration, which prioritizes economic and security dynamics over enduring alliances and strategic balances.

♦ Strategic Alignment:

Khartoum should work to join the new strategic alliance that Ankara is forming with countries in the Horn of Africa—an initiative that is nearing implementation. These partnerships will help Sudan solidify its national legitimacy and further isolate the RSF from regional and international political engagement, weakening its overall influence.

♦ At the African Level:

Accelerate the formation of a Sudan-led security coalition to combat all armed groups threatening national states. Given Sudan’s own extensive experience in confronting such militias, it is well-positioned to lead this effort. This strategy could involve strengthening ties with African nations like Nigeria, Cameroon, and Ghana—all of which face similar threats.

These countries have shown growing interest in security cooperation with Sudan, particularly after the Sudanese Army’s successful neutralization of the RSF and the liberation of Khartoum.

Security collaboration with nations like Nigeria will not only bolster Sudan’s own national security but also encourage other African states to join this collective security initiative.

♦ Gulf Cooperation:

Efforts should be made to convince Kuwait, Riyadh, and Doha—who are closest to the Sudanese public sentiment—of the importance of persuading the rest of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) to adopt a unified Gulf policy that supports the future of a united national state in Sudan. This would help confront the rapid developments unfolding in the Sudanese crisis, which may lead to new alliances forming in East Africa.

If Gulf diplomacy fails to act proactively and reach a unified stance, it may find itself isolated in the face of these emerging alliances. This could ultimately force a re-evaluation of Gulf perspectives on the future of Africa.

What is most concerning is that divergent political views among GCC countries regarding Sudan and other African files could lead to conflicting policies—“politiques de contradiction”—which would threaten the future of Gulf-African relations altogether.

♦ Intelligence Coordination:

Engage with the work of Dan Dunham, the former head of the Africa cell at the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff and one of the foremost experts on African affairs within the U.S. administration. He has shown serious intent in resolving the Sudanese crisis, particularly after the liberation of Khartoum.

His views appear closely aligned with those of Brendan McNamara, a prominent security figure within U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM) who supports the pro-people movements across the African continent.

Dr. Amina Al-Arimi

An Emirati researcher specializing in African affairs.