African politicians and some former security leaders recall an episode from the 1980s, in which a private meeting was held between the Somali Minister of National Security at the time, Ahmed Abdallah Youssouf, and the former Sudanese Minister of Interior, General Abdel Rahman Farah. Farah reportedly began the conversation by stating: “The American press portrays the Khartoum–Mogadishu relationship as an unacknowledged tension, and I believe they need to exercise greater accuracy in this assessment.” Youssouf replied: “Your relations with Washington are excellent, and consulting them on what their press reports seems straightforward—unless you have decided to turn eastward?” Farah responded: “Let us set aside our ideological differences and continue pursuing what we aim to achieve in the region. Are you ready?” Youssouf concluded: “Somalia is ready, provided Sudan is convinced that the key to its security requires consultation with Mogadishu.”

General Abdel Rahman conveyed this message to his leadership in Khartoum, then headed by President Jaafar Nimeiri. Despite his strong commitment to the success of the “Eastern Allies” project, the pressures directed at Khartoum to abort the initiative were greater than what the Sudanese leadership could bear, especially amid what French intelligence termed a “Déséquilibre politique” (political imbalance), which ultimately compelled Nimeiri to step down.

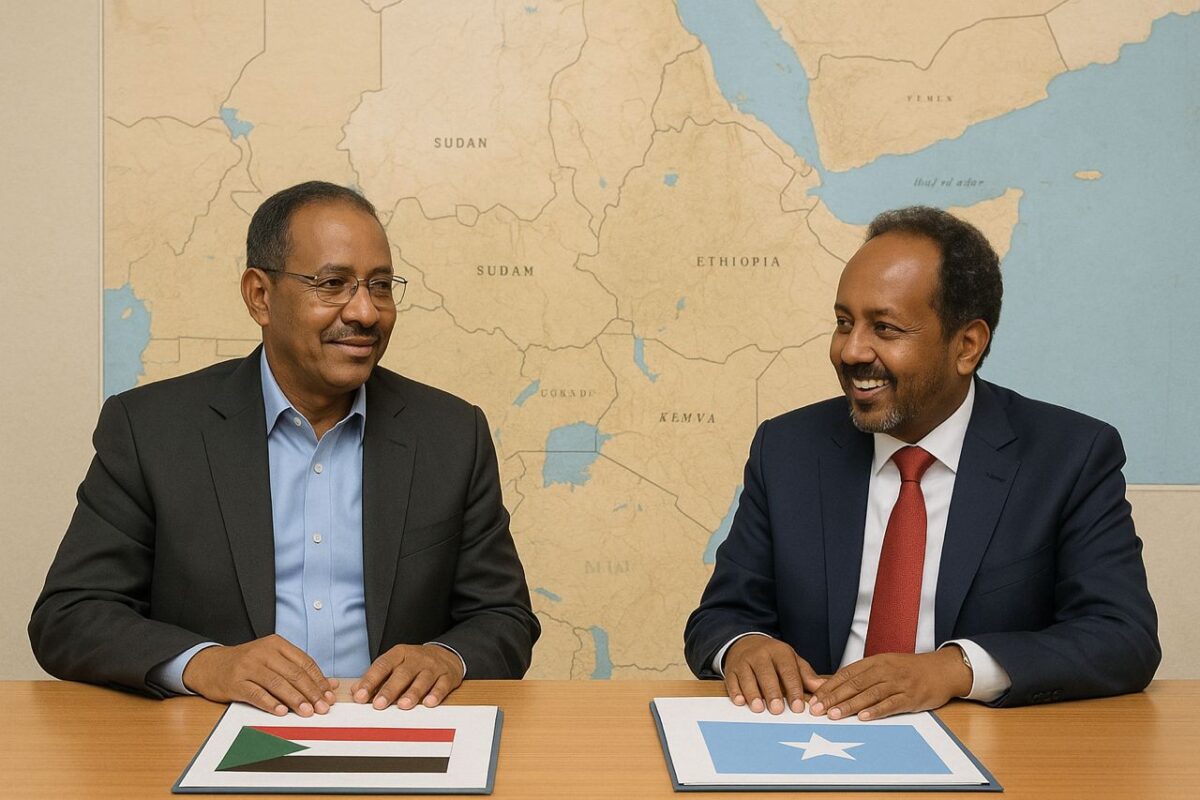

The recent visit of Lieutenant General Ahmed Ibrahim Ali Mufaddal, Director of the Sudanese National Intelligence Service, to the Federal Republic of Somalia reflects both security and political dimensions. It occurs in the context of the Sudanese leadership regaining control of state institutions. Given the multiple channels supplying military equipment to the Rapid Support Forces militias, Somalia’s Puntland region has emerged as one of the primary new supply routes. This situation necessitates that post-war Sudan “set directions, formulate visions, diversify mechanisms, and achieve objectives.”

Just as Sudan’s neighboring countries understand that the victory of the Sudanese army in this multinational, multi-directional, and multi-supply conflict had strategic, security, and political implications for their national security, they also recognize the limited resilience of their own institutions in facing a crisis similar to that experienced by the Sudanese army. This awareness highlights that a new “balance of power” is emerging—something Khartoum must strategically address today.

Khartoum recognizes that the Somali state, in its current configuration, lacks the capacity to prevent military supplies from reaching the Rapid Support Forces from its territory. This presents an opportunity for Khartoum to revive the “Eastern Allies” program, initially proposed by Sudanese leadership in the 1980s but suspended for “political reasons.”

Following the Sudanese military’s success in defeating the rebellion and restoring state authority, Khartoum must focus on key points and strengthen all means to translate them into a strategy enhancing national and regional security:

Neighboring countries understand that a new balance of power is forming in the Horn of Africa. Cooperation and coordination in the national interest are preferable. The success of the Sudanese Armed Forces in managing this multinational, multi-directional, multi-supply conflict has strategic, security, and political ramifications for all regional neighbors, who fully comprehend the limited resilience of their institutions under similar crises. This underscores the authority and prestige of Sudanese state institutions, which are now the primary and sole entities capable of achieving national consensus. To strengthen this, the following is proposed:

Establish a regional tactical training center based in Khartoum, including countries from the Horn of Africa and the Great Lakes region. Its mission would include the exchange of security and military expertise, the implementation of operational mechanisms to strengthen member states’ security, the development of strategies to combat terrorism and armed groups undermining national sovereignty, and the organization of lectures and workshops for researchers and security and political specialists.

Monitor the “security ebb and flow” between Ethiopia and Somalia. If Khartoum succeeds in managing these fluctuations, it will be possible to cut off military supply sources to the Rapid Support Forces. It is also important to understand the “Liyu Police,” a paramilitary group in the Somali Region of Ethiopia, established in coordination with Ethiopian security to neutralize the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF). Following deteriorating Somali–Ethiopian relations, some Liyu Police members joined Jubaland administration along with former ONLF members, despite the 2018 peace agreement. Having found no tangible benefits, they moved to Jubaland to fight Al-Shabaab for financial compensation. This explains the appointment of Colonel Khalid Sheikh Omar as commander of the Somali army infantry in November 2024, due to his previous role as head of Jubaland intelligence and his Liyu Police background. These developments led Addis Ababa to reposition Ethiopian defense forces from northern Harar to the eastern command in Gode, aiming to demonstrate the administration’s ability to secure borders against threats, including potential Egyptian forces within the AU Stabilization Mission in Somalia (AUSSOM). Ongoing instability along the Somali–Ethiopian border facilitates arms trafficking in the region.

I consider that, despite the uncertainty surrounding its scope, the revival of the “Eastern Allies” project is increasingly feasible given the security and political developments in the Horn of Africa and Sudan, particularly when considering the Sudan–Eritrea rapprochement, the Eritrea–Somalia axis, and Ethiopia’s oscillations driven by existential and corrective imperatives.

Dr. Ameena Alarimi

Emirati Researcher on African Affairs

No Comments