At the height of the Ethiopian-Egyptian tension over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam on the one hand, and the apprehension saturated with ill will between Djibouti and Eritrea on the other, and the Kenyan-Somali dispute over the maritime border on the third hand, I was monitoring what was written in the official press in all those countries. And not only that, but I also intensified my hours of cultural council, which I held at my home one day a week with the most competent African elites, some of whom I met during my studies, some through field work in the African continent, some of whom succeeded in representing African diplomacy in some Gulf capitals, and some of whom were driven by curiosity to know who is that Gulf woman who left the comfort of her society and headed to roam the wilds of Africa until our land became addicted to her, our youth knew her, and she mastered part of our culture. Even if she did not participate in it, is she a daughter of Africa that it did not give birth to? And this is what we hope for? Or is she being directed by some side, and this is what we fear? After a full decade of these questions, I find the same eyes that once looked at me with questioning doubt now filled with reassurance and comfort, as their hopes have been proven true.

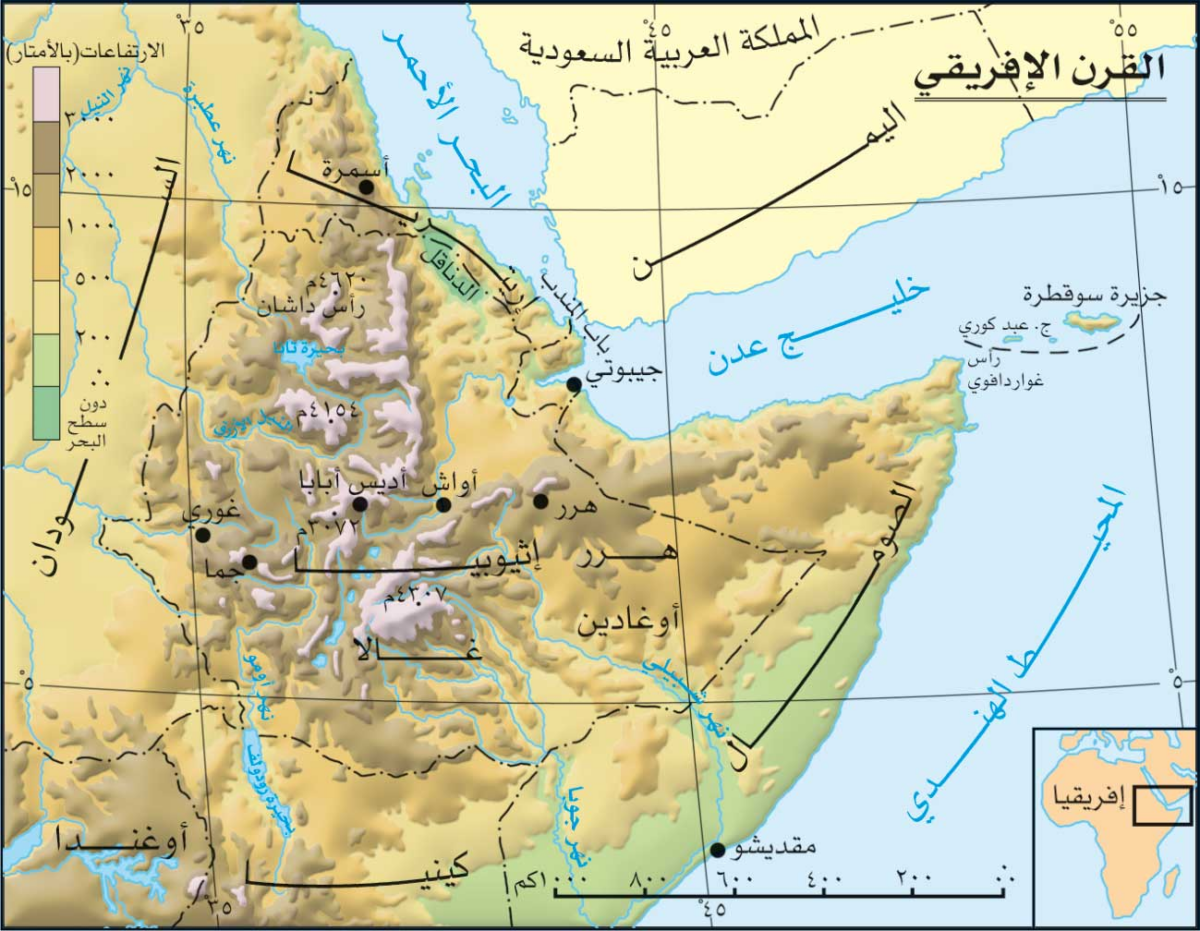

African colleagues, especially in the Horn of Africa, often discuss with me the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries’ perspectives on the renewed tensions between Addis Ababa and Cairo, Asmara and Djibouti, and Mogadishu and Nairobi. They wonder why we don’t see a detailed report in the Gulf press from Gulf elites on what is actually happening in our countries, based on sound scientific evidence. My answer is that the Gulf reader’s reluctance, first and foremost, to closely understand the African field situation and to read the original African references issued by the scientific and intellectual elites who abound in the Horn of Africa region, to understand the causes of these stifling tensions prevailing in the Horn of Africa, is the obstacle that has always stood in the way of the Gulf’s understanding of the nature of Africa and the Horn of Africa and what is happening there. This has affected the Gulf’s assessment of the African reality and the political, social, and economic rifts that afflict it. Consequently, there has been no genuine scientific Gulf vision for the Horn of Africa, let alone the rest of sub-Saharan Africa.

Today’s international powers do not want to escalate tensions in the Horn of Africa. On the one hand, they do not want an escalation in the Ethiopian-Egyptian issue and will not allow it to escalate beyond media statements that do not serve the future of the Nile River or the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, as much as they incite hostility unbecoming of the peoples of the Nile Basin countries. On the other hand, they do not want the escalation of the apprehension saturated with ill-intentioned intentions between Asmara and Djibouti to impose a reality and return the region to 2008 (the events of Tel el-Barr and the island of Djibouti). On the other hand, it does not want any kind of Kenyan-Somali tension to escalate. Rather, it wants to maintain the issues of the new Somalia, the model for which has been drawn up, coinciding with the forgiveness of Mogadishu’s debts and the return of the US embassy to Somalia after a three-decade hiatus. At the same time, it wants to maintain Nairobi’s position as a supporter of the international powers’ strategies on all issues (terrorism, economy, energy).

The Horn of Africa region is currently being contested by international axes interspersed with regional powers, and coordination between them has reached advanced stages on some issues. Between these major axes and the emerging regional powers, the Gulf Cooperation Council countries are the weakest link in this conflict, and today they are faced with only a set of possible scenarios in the Horn of Africa region.

The first scenario: Federal Somalia is an emerging force, following Washington’s reopening of its embassy in Mogadishu after decades of closure, followed by the forgiveness of Somalia’s financial debts. All of this indicates the imminent occurrence of radical political changes in Somalia, with which Washington is paving the way for its strategy for a new Horn of Africa and preparing Mogadishu to play a new role it has not yet achieved. The Horn of Africa region is composed of Somalia. Here, either some Gulf states will find themselves settling scores with Mogadishu, which is angry about some Gulf trends, or the Gulf states will find themselves facing a new rival possessing superior natural resources, manpower, and a strategic location, qualifying it to play a strong competitor in the Gulf of Aden, the Indian Ocean, and the Arabian Sea.

Second Scenario: Isolating each Gulf state from the others. It is likely that international powers will work to prevent the return of Gulf reconciliation so that they can isolate each Gulf state from the others and exploit this Gulf discord to suit their interests. This is especially true since there are certain issues in the Horn of Africa and Sudan that international powers do not want to appear to the public as being responsible for managing. Even if the matter is exposed, there is one party that bears responsibility and must pay the price, exposing Gulf interests to further targeting and erosion.

Third Scenario: Somali-Turkish Progress. It is likely that security and military cooperation in the Horn of Africa will increase between Turkey, Somalia, and some Gulf states, and Ethiopia, Kenya, and Sudan may join them in the future on some issues or at some stage. The stages, and in light of the diverging political visions of each Gulf state and the future role that each Gulf state desires for itself, in isolation from the others, will naturally lead to further conflict between the Gulf states, not only in the Horn of Africa, but may also extend to the entire African continent, further undermining the idea of a Gulf Union.

Fourth Scenario: The easing of the Ethiopian-Egyptian issue. The escalation of Egyptian-Ethiopian disagreements over the Renaissance Dam may exacerbate the division between the Gulf states. Here, either Cairo will find itself alone without real Gulf support, or some of the Gulf states allied with Cairo will abandon Ethiopia and form a front with Egypt. This is something I rule out. The Arab Gulf states, even those allied with Cairo, do not want to lose Ethiopia, but they may contribute to bringing the Egyptian and Ethiopian sides closer together to resolve the dispute between them without losing either party. This will limit the chances of success.

Dr. Amina Al-Arimi

An Emirati researcher specializing in African affairs.